This article was last updated on May 23, 2024 to add more informations, new sections for performance of useState hook.

Introduction

The most challenging aspect of developing any application is often managing its state. However, we are often required to manage several pieces of state in our application, such as when data is retrieved from an external server or updated in the app.

The difficulty of state management is the reason why so many state management libraries exist today - and more are still being developed. Thankfully, React has several built-in solutions in the form of hooks for state management, which makes managing states in React easier.

It's no secret that hooks have become increasingly crucial in React component development, particularly in functional components, as they have entirely replaced the need for class-based components, which were the conventional way to manage stateful components. The useState hook is one of many hooks introduced in React, but although the useState hook has been around for a few years now, developers are still prone to making common mistakes due to inadequate understanding.

The useState hook can be tricky to understand, especially for newer React developers or those migrating from class-based components to functional components. In this guide, we'll explore the top 5 common useState mistakes that React developers often make and how you can avoid them.

Steps we'll cover:

- What is React useState?

- Initializing useState Wrongly

- Not Using Optional Chaining

- Updating useState Directly

- Updating Specific Object Property

- Managing Multiple Input Fields in Forms

- Bonus: Optimize performance when using useState

- Bonus: use

useReducerfor complex state management

What is React useState?

We would like to describe shortly the useState hook in React, which we use very often in all of our projects. The useState hook is one of the fundamental hooks. With it, we can introduce state variables into our functional components. The hook returns an array with two elements: the current state value and a function to maintain or set that value.

Here's an example:

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

In the above code, count is a state variable, and setCount is a function to update it. Whenever we need to change that state, we call setCount with the new value. It is just a way to deal with state easily in your components without class components.

We love useState because it allows us to keep our components super clean and very easy to read. It's one of the main reasons why functional components are such a powerful feature in React.

Initializing useState Wrongly

Initiating the useState hook incorrectly is one of the most common mistakes developers make when utilizing it. What does it mean to initialize useState? To initialize something is to set its initial value.

The problem is that useState allows you to define its initial state using anything you want. However, what no one tells you outright is that depending on what your component is expecting in that state, using a wrong date type value to initialize your useState can lead to unexpected behavior in your app, such as failure to render the UI, resulting in a blank screen error.

For example, we have a component expecting a user object state containing the user's name, image, and bio - and in this component, we are rendering the user's properties.

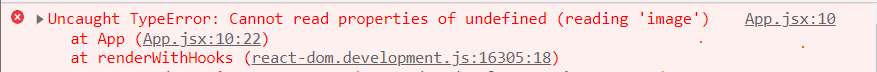

Initializing useState with a different data type, such as an empty state or a value, would result in a blank page error, as shown below.

import { useState } from "react";

function App() {

// Initializing state

const [user, setUser] = useState();

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<img

src="https://refine.ams3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.comundefined"

alt="profile image"

/>

<p>User: {user.name}</p>

<p>About: {user.bio}</p>

</div>

);

}

export default App;

Output:

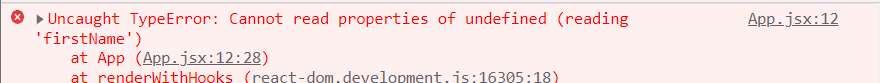

Inspecting the console would throw a similar error as shown below:

Newer developers often make this mistake when initializing their state, especially when fetching data from a server or database, as the retrieved data is expected to update the state with the actual user object. However, this is bad practice and could lead to expected behavior, as shown above.

The preferred way to initialize useState is to pass it the expected data type to avoid potential blank page errors. For example, an empty object, as shown below, could be passed to the state:

import { useState } from "react";

function App() {

// Initializing state with expected data type

const [user, setUser] = useState({});

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<img

src="https://refine.ams3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.comundefined"

alt="profile image"

/>

<p>User: {user.name}</p>

<p>About: {user.bio}</p>

</div>

);

}

export default App;

Output:

We could take this a notch further by defining the user object's expected properties when initializing the state.

import { useState } from "react";

function App() {

// Initializing state with expected data type

const [user, setUser] = useState({

image: "",

name: "",

bio: "",

});

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<img

src="https://refine.ams3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.comundefined"

alt="profile image"

/>

<p>User: {user.name}</p>

<p>About: {user.bio}</p>

</div>

);

}

export default App;

Not Using Optional Chaining

Sometimes just initializing the useState with the expected data type is often not enough to prevent the unexpected blank page error. This is especially true when trying to access the property of a deeply nested object buried deep inside a chain of related objects.

You typically try to access this object by chaining through related objects using the dot (.) chaining operator, e.g., user.names.firstName. However, we have a problem if any chained objects or properties are missing. The page will break, and the user will get a blank page error.

For Example:

import { useState } from "react";

function App() {

// Initializing state with expected data type

const [user, setUser] = useState({});

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<img

src="https://refine.ams3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.comundefined"

alt="profile image"

/>

<p>User: {user.names.firstName}</p>

<p>About: {user.bio}</p>

</div>

);

}

export default App;

Output error:

A typical solution to this error and UI not rendering is using conditional checks to validate the state's existence to check if it is accessible before rendering the component, e.g., user.names && user.names.firstName, which only evaluates the right expression if the left expression is true (if the user.names exist). However, this solution is a messy one as it would require several checks for each object chain.

Using the optional chaining operator (?.), you can read the value of a property that is buried deep inside a related chain of objects without needing to verify that each referenced object is valid. The optional chaining operator (?.) is just like the dot chaining operator (.), except that if the referenced object or property is missing (i.e., or undefined), the expression short-circuits and returns a value of undefined. In simpler terms, if any chained object is missing, it doesn't continue with the chain operation (short-circuits).

For example, user?.names?.firstName would not throw any error or break the page because once it detects that the user or names object is missing, it immediately terminates the operation.

import { useState } from "react";

function App() {

// Initializing state with expected data type

const [user, setUser] = useState({});

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<img

src="https://refine.ams3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.comundefined"

alt="profile image"

/>

<p>User: {user?.names?.firstName}</p>

<p>About: {user.bio}</p>

</div>

);

}

export default App;

Taking advantage of the optional chaining operator can simplify and shorten the expressions when accessing chained properties in the state, which can be very useful when exploring the content of objects whose reference may not be known beforehand.

Updating useState Directly

The lack of proper understanding of how React schedules and updates state can easily lead to bugs in updating the state of an application. When using useState, we typically define a state and directly update the state using the set state function.

For example, we create a count state and a handler function attached to a button that adds one (+1) to the state when clicked:

import { useState } from "react";

function App() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

// Directly update state

const increase = () => setCount(count + 1);

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<span>Count: {count}</span>

<button onClick={increase}>Add +1</button>

</div>

);

}

export default App;

The output:

This works as expected. However, directly updating the state is a bad practice that could lead to potential bugs when dealing with a live application that several users use. Why? Because contrary to what you may think, React doesn't update the state immediately when the button is clicked, as shown in the example demo. Instead, React takes a snapshot of the current state and schedules this Update (+1) to be made later for performance gains - this happens in milliseconds, so it is not noticeable to the human eyes. However, while the scheduled Update is still in pending transition, the current state may be changed by something else (such as multiple users' cases). The scheduled Update would have no way of knowing about this new event because it only has a record of the state snapshot it took when the button got clicked.

This could result in major bugs and weird behavior in your application. Let’s see this in action by adding another button that asynchronously updates the count state after a 2 seconds delay.

import { useState } from "react";

function App() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

// Directly update state

const update = () => setCount(count + 1);

// Directly update state after 2 sec

const asyncUpdate = () => {

setTimeout(() => {

setCount(count + 1);

}, 2000);

};

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<span>Count: {count}</span>

<button onClick={update}>Add +1</button>

<button onClick={asyncUpdate}>Add +1 later</button>

</div>

);

}

Pay attention to the bug in the output:

Notice the bug? We start by clicking on the first "Add +1" button twice (which updates the state to 1 + 1 = 2). After which, we click on the "Add +1 later" – this takes a snapshot of the current state (2) and schedules an update to add 1 to that state after two seconds. But while this scheduled update is still in transition, we went ahead to click on the "Add +1" button thrice, updating the current state to 5 (i.e., 2 + 1 + 1 + 1 = 5). However, the asynchronous scheduled Update tries to update the state after two seconds using the snapshot (2) it has in memory (i.e., 2 + 1 = 3), not realizing that the current state has been updated to 5. As a result, the state is updated to 3 instead of 6.

This unintentional bug often plagues applications whose states are directly updated using just the setState(newValue) function. The suggested way of updating useState is by functional update which to pass setState() a callback function and in this callback function we pass the current state at that instance e.g., setState(currentState => currentState + newValue). This passes the current state at the scheduled update time to the callback function, making it possible to know the current state before attempting an update.

So, let's modify the example demo to use a functional update instead of a direct update.

import { useState } from "react";

function App() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

// Directly update state

const update = () => setCount(count + 1);

// Directly update state after 3 sec

const asyncUpdate = () => {

setTimeout(() => {

setCount((currentCount) => currentCount + 1);

}, 2000);

};

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<span>Count: {count}</span>

<button onClick={update}>Add +1</button>

<button onClick={asyncUpdate}>Add +1 later</button>

</div>

);

}

export default App;

Output:

With functional update, the setState() function knows the state has been updated to 5, so it updates the state to 6.

Updating Specific Object Property

Another common mistake is modifying just the property of an object or array instead of the reference itself.

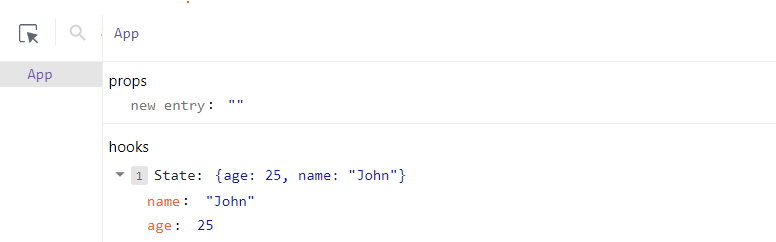

For example, we initialize a user object with a defined "name" and "age" property. However, our component has a button that attempts to update just the user's name, as shown below.

import { useState, useEffect } from "react";

export default function App() {

const [user, setUser] = useState({

name: "John",

age: 25,

});

// Update property of user state

const changeName = () => {

setUser((user) => (user.name = "Mark"));

};

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<p>User: {user.name}</p>

<p>Age: {user.age}</p>

<button onClick={changeName}>Change name</button>

</div>

);

}

Initial state before the button is clicked:

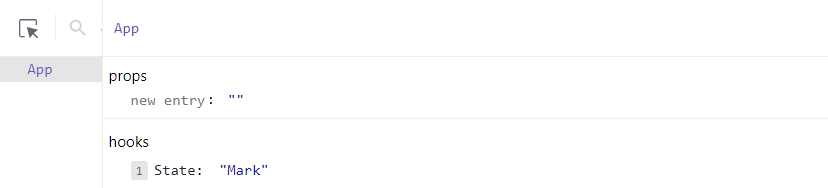

Updated state after the button is clicked:

As you can see, instead of the specific property getting modified, the user is no longer an object but has been overwritten to the string “Mark”. Why? Because setState() assigns whatever value returned or passed to it as the new state. This mistake is common with React developers migrating from class-based components to functional components as they are used to updating state using this.state.user.property = newValue in class-based components.

One typical old-school way of doing this is by creating a new object reference and assigning the previous user object to it, with the user’s name directly modified.

import { useState, useEffect } from "react";

export default function App() {

const [user, setUser] = useState({

name: "John",

age: 25,

});

// Update property of user state

const changeName = () => {

setUser((user) => Object.assign({}, user, { name: "Mark" }));

};

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<p>User: {user.name}</p>

<p>Age: {user.age}</p>

<button onClick={changeName}>Change name</button>

</div>

);

}

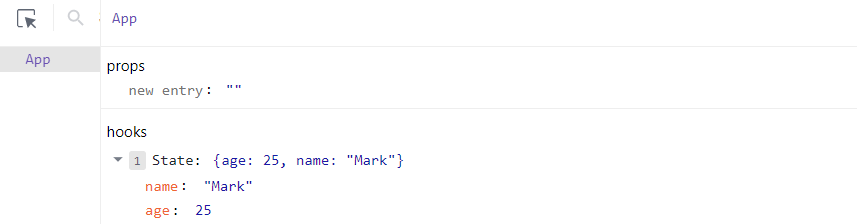

Updated state after the button is clicked:

Notice that just the user’s name has been modified, while the other property remains the same.

However, the ideal and modern way of updating a specific property or an object or array is the use of the ES6 spread operator (...). It is the ideal way to update a specific property of an object or array when working with a state in functional components. With this spread operator, you can easily unpack the properties of an existing item into a new item and, at the same time, modify or add new properties to the unpacked item.

import { useState, useEffect } from "react";

export default function App() {

const [user, setUser] = useState({

name: "John",

age: 25,

});

// Update property of user state using spread operator

const changeName = () => {

setUser((user) => ({ ...user, name: "Mark" }));

};

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<p>User: {user.name}</p>

<p>Age: {user.age}</p>

<button onClick={changeName}>Change name</button>

</div>

);

}

The result would be the same as the last state. Once the button is clicked, the name property is updated while the rest of the user properties remain the same.

Managing Multiple Input Fields in Forms

Managing several controlled inputs in a form is typically done by manually creating multiple useState() functions for each input field and binding each to the corresponding input field. For example:

import { useState, useEffect } from "react";

export default function App() {

const [firstName, setFirstName] = useState("");

const [lastName, setLastName] = useState("");

const [age, setAge] = useState("");

const [userName, setUserName] = useState("");

const [password, setPassword] = useState("");

const [email, setEmail] = useState("");

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<form>

<input type="text" placeholder="First Name" />

<input type="text" placeholder="Last Name" />

<input type="number" placeholder="Age" />

<input type="text" placeholder="Username" />

<input type="password" placeholder="Password" />

<input type="email" placeholder="email" />

</form>

</div>

);

}

Furthermore, you have to create a handler function for each of these inputs to establish a bidirectional flow of data that updates each state when an input value is entered. This can be rather redundant and time-consuming as it involves writing a lot of code that reduces the readability of your codebase.

However, it's possible to manage multiple input fields in a form using only one useState hook. This can be accomplished by first giving each input field a unique name and then creating one useState() function that is initialized with properties that bear identical names to those of the input fields.

import { useState, useEffect } from "react";

export default function App() {

const [user, setUser] = useState({

firstName: "",

lastName: "",

age: "",

username: "",

password: "",

email: "",

});

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<form>

<input type="text" name="firstName" placeholder="First Name" />

<input type="text" name="lastName" placeholder="Last Name" />

<input type="number" name="age" placeholder="Age" />

<input type="text" name="username" placeholder="Username" />

<input type="password" name="password" placeholder="Password" />

<input type="email" name="email" placeholder="email" />

</form>

</div>

);

}

After which, we create a handler event function that updates the specific property of the user object to reflect changes in the form whenever a user types in something. This can be accomplished using the spread operator and dynamically accessing the name of the specific input element that fired the handler function using the event.target.elementsName = event.target.value.

In other words, we check the event object that is usually passed to an event function for the target elements name (which is the same as the property name in the user state) and update it with the associated value in that target element, as shown below:

import { useState, useEffect } from "react";

export default function App() {

const [user, setUser] = useState({

firstName: "",

lastName: "",

age: "",

username: "",

password: "",

email: "",

});

// Update specific input field

const handleChange = (e) =>

setUser((prevState) => ({ ...prevState, [e.target.name]: e.target.value }));

// Render UI

return (

<div className="App">

<form>

<input

type="text"

onChange={handleChange}

name="firstName"

placeholder="First Name"

/>

<input

type="text"

onChange={handleChange}

name="lastName"

placeholder="Last Name"

/>

<input

type="number"

onChange={handleChange}

name="age"

placeholder="Age"

/>

<input

type="text"

onChange={handleChange}

name="username"

placeholder="Username"

/>

<input

type="password"

onChange={handleChange}

name="password"

placeholder="Password"

/>

<input

type="email"

onChange={handleChange}

name="email"

placeholder="email"

/>

</form>

</div>

);

}

With this implementation, the event handler function is fired for each user input. In this event function, we have a setUser() state function that accepts the previous/current state of the user and unpacks this user state using the spread operator. Then we check the event object for whatever target element name that fired the function (which correlates to the property name in the state). Once this property name is gotten, we modify it to reflect the user input value in the form.

Bonus: Optimize performance when using useState

We wanted to give you a heads-up on some tips to optimize performance when using useState within a React application. With every useState, by default, every state change of our component will re-render. That is completely cool and normally works fine.

In larger and more complex applications, this could—in the worst-case scenario—become a performance bottleneck, and one way to optimize that is by using functional updates. If your new state depends on the previous state, then using a function for updates ensures no unnecessary renders with setState. Here's a quick example:

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const increment = () => {

setCount((prevCount) => prevCount + 1);

};

And another great tip to always remember is: Try and keep the number of state variables in your application to a minimum. Group related parts of your state to one state object, using an object instead of multiple calls to useState. This can really help reduce the number of renders and make your code more manageable.

Finally, React.memo for functional components or PureComponent for class components will prevent re-renders if props or state don't change.

Optimizing how state is managed with useState will bring a huge performance gain to our app, providing more speed and a better user experience.

Bonus: use useReducer for complex state management

Another great pro tip on dealing with complex state in React is to use useReducer. Even though useState is awesome for dealing with simple state, useReducer can sometimes be more efficient for dealing with bigger state logic. Pretty much useReducer. It acts identically to useState but lets us deal with state transitions through a reducer function.

This is helpful in two cases: either the state has sub-values or the next state depends on the previous one. Here is a quick example:

const initialState = { count: 0 };

function reducer(state, action) {

switch (action.type) {

case "increment":

return { count: state.count + 1 };

case "decrement":

return { count: state.count - 1 };

default:

throw new Error();

}

}

const [state, dispatch] = useReducer(reducer, initialState);

const increment = () => {

dispatch({ type: "increment" });

};

const decrement = () => {

dispatch({ type: "decrement" });

};

In this way, the code becomes much cleaner and maintainable when using useReducer. Also, it's quite similar to what's happening in Redux, so this is a great stepping stone if you're going to use Redux in the future. I find useReducer extremely helpful for managing complex states. It has worked wonders in terms of maintainability and readability for our code.

Conclusion

As a React developer creating highly interactive user interfaces, you have probably made some of the mistakes mentioned above. Hopefully, these helpful useState practices will help you avoid some of these potential mistakes while using the useState hook down the road while building your React-powered applications.